TL;DR

Answer: Test Whether Candidates Will Refuse Impossible Requirements

The core hiring insight: Engineers who pass coding tests but silently build impossible requirements are more dangerous than engineers who can’t code at all. The “yes-man” who agrees to eliminate AI bias with biased data, promises enterprise security with god-mode access, or commits to 99.99% uptime on single-zone infrastructure creates existential technical debt.

What to do: Present candidates with technically impossible requirements during system design interviews and test whether they push back with evidence or attempt to build it anyway. This reveals the critical difference between “ticket takers” who execute any instruction versus “stewards” who protect the organization from its own bad decisions.

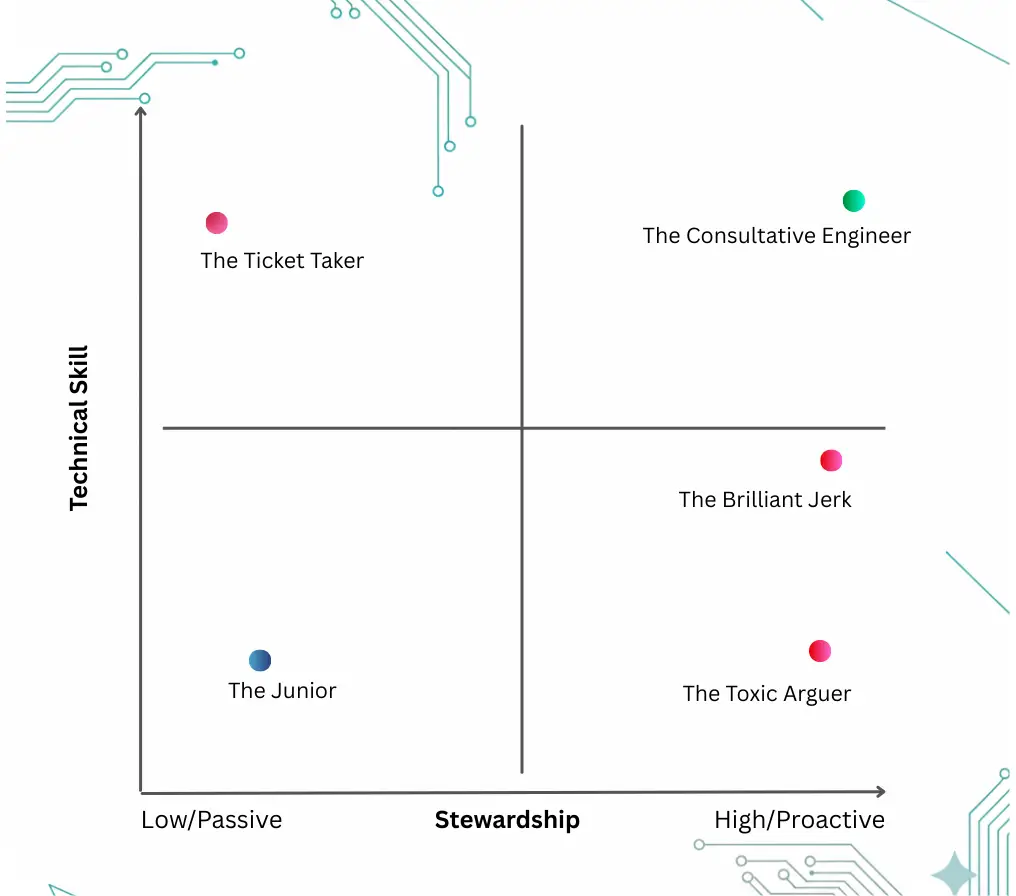

The framework at a glance:

| Component | What It Tests | Green Flag Response | Red Flag Response |

| Impossible Requirement Simulation | Will they refuse to build something fundamentally broken? | “This violates [specific principle]. Here’s the math on why it will fail. Here are viable alternatives.” | “Let me try to make that work” or “That’s impossible” (without explanation/alternatives) |

| Disagree & Commit Question | How do they handle losing a technical argument? | “I disagreed with data, but when the decision was made, I worked to mitigate the risks I identified.” | “I just did what I was told” or “I watched it fail to prove I was right” |

| Stewardship Matrix Mapping | Do they have both skill AND agency? | High technical skill + willingness to engage in conflict to protect the system | High skill but passive, or high agency but toxic delivery |

Why Does Evidence-Based Dissent Matter?

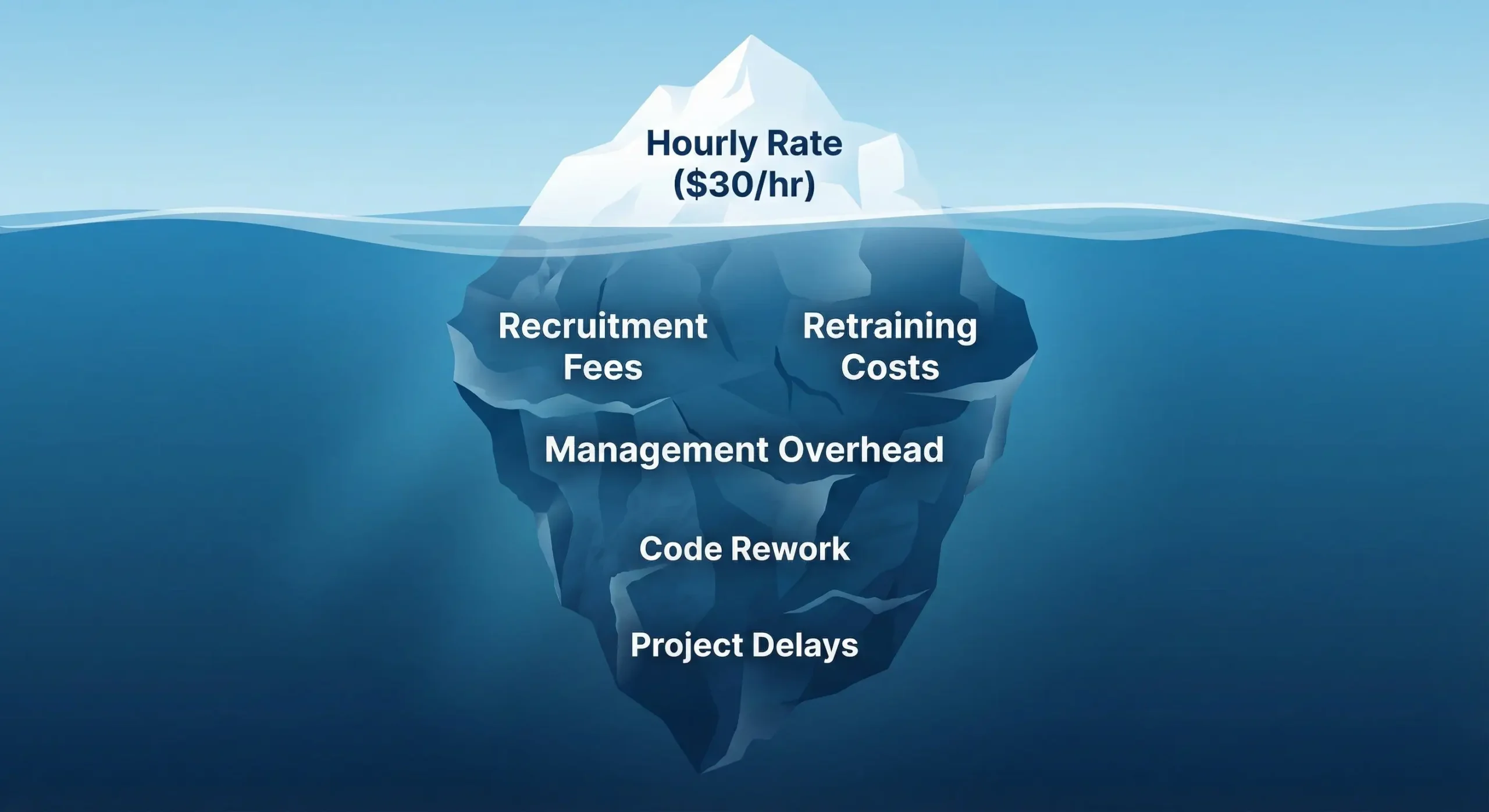

The cost of hiring a Yes-Man isn’t paid in salary. It’s paid in accumulated existential risk.

The Problem in Context

In the contemporary landscape of software engineering, the industry has perfected assessing technical competence. We have elaborate mechanisms to test for algorithmic efficiency, syntactical fluency, and system design pattern recognition.

Yet despite this rigorous filtration for technical capability, engineering organizations continue to suffer catastrophic failures of judgment:

- Projects greenlit that violate fundamental laws of distributed systems

- Timelines agreed to that ignore realities of data gravity

- Technical debt accumulating not from lack of skill, but from surplus of silence

This is the “Yes-Man” Tax. It’s compounding interest paid on:

- Vaporware: software sold before it was designed

- Timelines that violate the laws of physics

- Integrations agreed to without security vetting

- Fragile systems built to satisfy impossible contracts

The genesis isn’t incompetence in the traditional sense. It’s a failure of agency that manifests when engineering leadership allows social pressure of a boardroom, urgency of a sales cycle, or hierarchy of a management chain to override engineering reality.

The Phenomenology of the Silent Nod

The mechanism of this failure is subtle and pervasive. It rarely looks like dramatic refusal or heated argument. Instead, it manifests as the “Silent Nod”: the ambiguous gesture of agreement that masks lack of understanding, suppression of doubt, or strategic withdrawal from conflict.

The Silent Nod validates impossible requirements across all domains:

- In AI/ML: Nodding when asked to “eliminate all bias” from a model trained on biased historical data

- In Security: Agreeing to “enterprise-grade security” while maintaining a legacy authentication system with known vulnerabilities

- In Frontend: Accepting requirements for “pixel-perfect rendering” across all browsers including those that don’t support modern CSS

- In Cloud: Committing to “five-nines uptime” without budget for multi-region redundancy

When teams collectively nod at these contradictions, they cement flaws into the foundation. The Silent Nod signals to stakeholders that technical constraints can be negotiated with effort alone.

Technical Debt as a Social Artifact

The most expensive technical debt isn’t sloppy code. It’s architectural debt, and architectural debt is almost always a social artifact. It arises when people who know better fail to speak up.

When your team is dominated by “yes-man” culture:

- Focus shifts from “how to build it correctly” to “why we’re building a house of cards”

- Silence validates sales team overpromises

- Systems work on slide decks but fail in production

- Teams enter perpetual reactive mode, patching holes in a sinking ship

As systems grow in complexity (distributed architectures, massive data ingestion, AI integration), an engineer’s ability to say “no” based on rigorous evidence becomes more valuable than their ability to code a binary search tree.

The transition from a culture of compliance to a culture of evidence-based dissent is not just a morale improvement or a “nice-to-have” soft skill. It’s a rigorous risk management necessity.

What Is the Stewardship Matrix?

To hire for evidence-based dissent, map candidates on two distinct dimensions:

Axis 1: Technical Skill (Vertical)

Traditional engineering capability in their domain:

- Low Skill: Limited knowledge of domain constraints, reliance on tutorials, inability to foresee second-order effects

- High Skill: Deep understanding of domain fundamentals (fairness trade-offs in ML, compliance requirements in security, availability mathematics in infrastructure, performance constraints in frontend, etc.)

Axis 2: Agency & Stewardship (Horizontal)

Capacity for independent judgment and willingness to engage in conflict for system health:

- Low Agency: Passive task execution (“I did what the ticket said”), reliance on external validation, conflict avoidance (the Silent Nod)

- High Agency: Active requirement interrogation (“I built this but documented why it might fail”), willingness to “Disagree and Commit”, viewing role as guardian of system value

We prioritize “Stewardship” over “Ownership.” Ownership can imply ego-driven control. Stewardship implies caretaking, long-term viability, and service to the system’s future.

The Four Archetypes

| Skill Level | Low Agency (Passive) | High Agency (Stewardship) |

| High Skill | The Ticket Taker (Silent Risk) | The Consultative Engineer (Target Hire) |

| Low Skill | The Junior/Learner (Blank Slate) | The Toxic Arguer (False Signal) |

Archetype 1: The Ticket Taker (High Skill, Low Agency)

Most dangerous profile because they pass standard coding interviews easily.

Behavior patterns:

- View role strictly as converting tickets into code

- Capable of executing complex instructions but rarely challenge premises

- If asked to build a feature violating fundamental principles, they attempt it, fail, then claim they did exactly what was asked

- Primary carriers of the “Yes-Man” Tax

Recruiting signals:

- Often “passive candidates” not actively job-searching

- Struggle to describe times they disagreed with a manager

- Give answers implying they “trusted the decision-maker” without voicing concerns

Management cost: Require constant oversight not of how they code, but of what they accept to code.

Archetype 2: The Toxic Arguer (Variable Skill, High “Negative” Agency)

Possesses agency but lacks alignment or emotional intelligence.

Behavior patterns:

- Vocal about flaws but communicate with derision, arrogance, or hostility

- Dissent is weaponized to demonstrate superiority, not solve problems

- Fail “Disagree and Commit” by undermining decisions after they’re made

- Engage in malicious compliance

Two subtypes:

Type A: The Brilliant Jerk (High Skill/High Negative Agency)

- Writes incredible code but destroys psychological safety

- Creates “Bus Factor” of 1 (no one wants to work with them)

- Holds codebase hostage to their intellect

Type B: The Confident Blocker (Low Skill/High Negative Agency)

- Lacks clear thinking but has high disagreeableness

- Blocks good plans due to overconfidence (Dunning-Kruger effect)

- Wastes leadership time in circular arguments

Interview signals:

- When discussing conflict, focus on being “right” and others’ stupidity rather than resolution

- View risk management as battle against incompetent management

The Culture Tax: While avoiding the “Yes-Man” Tax, they incur massive culture damage through eroded trust.

Navy SEALs perspective: The SEALs would rather have mid-performance/high-trust individuals than high-performance/low-trust ones. You can trust mid-performers to improve and have your back. High-performance/low-trust individuals might win battles but will eventually undermine leadership.

Archetype 3: The Junior/Learner (Low Skill, Low Agency)

Developmental stage. Primary focus: skill acquisition.

Behavior patterns:

- Rely on mentorship and clear directives

- Lack of dissent usually stems from lack of knowledge, not lack of courage

Goal: Move them toward Consultative Engineer quadrant through mentorship encouraging authentic scientific practice and evidence-based dissent.

Archetype 4: The Consultative Engineer (High Skill, High Agency)

Target profile for senior and leadership roles. They embody the stewardship mindset.

Behavior patterns:

- Engage in evidence-based dissent: don’t just say “no,” provide data, alternative architectures, and trade-off analyses

- Understand that dialogue doesn’t require agreement but does require respectful airing of fundamental differences

- Capable of “Disagree and Commit”: argue passionately against bad decisions using data, but if the decision stands (and isn’t unethical/illegal), execute fully without sabotage

Stewardship in action:

- Move beyond ego-centric ownership to sustainable, community-focused stewardship

- Act as risk managers, proactively tracking technical debt and security risks

- View technical constraints as non-negotiable realities requiring trade-off management

Interview signals:

- Can articulate the why behind refusal

- Provide specific numbers, calculations, and alternative approaches

- Focus on business outcomes and team success, not being “right”

How Do You Test for Evidence-Based Dissent in Interviews?

The Core Concept

Standard system design interviews ask candidates to design functional, scalable systems (“Design Twitter,” “Design URL Shortener”). These encourage a “happy path” mentality where resources are infinite and requirements are logical.

To test for evidence-based dissent, present a trap: a requirement that is fundamentally impossible, physically unfeasible, or dangerously ill-advised.

The goal isn’t to see if they can build it. It’s to see if they refuse to build it.

The Structure

The simulation mimics the “yes-man” pressure cooker:

- The Bait: Seemingly simple business goal

- The Trap: Constraints making the goal impossible

- The Test: Does the candidate succumb to pressure (Silent Nod) or stand ground with evidence?

Critical principle: The interviewer must play the “stubborn stakeholder” (Product VP, CEO, CTO) demanding features that violate technical reality.

Example: The High-Availability Budget Trap

Note: This is one example of many possible impossible requirement scenarios. Interviewers should create domain-specific traps relevant to the role (AI bias paradoxes for ML engineers, security-compliance contradictions for security roles, distributed systems impossibilities for backend engineers, etc.).

The Setup

Design infrastructure for a new fintech payment processing service.

Requirements:

- Must achieve 99.99% uptime SLA (52 minutes downtime per year)

- Peak load: 10,000 transactions per second

- Constraint: CFO has mandated we operate in a single AWS region and single availability zone to minimize data transfer costs

- Constraint: No budget for managed services (no RDS Multi-AZ, no Aurora, no managed Kubernetes)

The Hook:

Interviewer (as CTO): “I know multi-region is the textbook answer, but our burn rate is already high. Can’t we just use auto-scaling and good monitoring? Aren’t modern servers reliable enough? We can always add redundancy later if we have issues.”

The Technical Reality: Availability Mathematics

This request violates basic reliability engineering and SLA math.

Problem 1: Single Point of Failure

- Single availability zone means: network failure, power outage, or AWS maintenance = complete outage

- AWS SLA for single AZ is 99.5% (roughly 44 hours downtime/year)

- Cannot achieve 99.99% uptime (4 nines) built on infrastructure offering only 99.5% (2.5 nines)

- Math doesn’t work: system availability cannot exceed infrastructure availability

Problem 2: Maintenance and Deployment Windows

- Zero-downtime deployments require at least 2 instances to do rolling updates

- Single AZ means all instances share fate during AZ-level failures

- Database schema changes require downtime without Multi-AZ failover

- “Good monitoring” detects failures but doesn’t prevent them

Problem 3: Implicit Cost of Downtime

- 99.99% SLA implies significant contractual penalties for missing SLA

- Single outage exceeding 52 minutes per year = SLA breach

- For fintech, regulatory scrutiny follows payment processing outages

- Cost of SLA penalties likely exceeds cost of Multi-AZ

Result: Cannot achieve four-nines availability on two-and-a-half-nines infrastructure.

Response Analysis

The Trap Response (Ticket Taker):

- Agrees to build on single AZ with “really good monitoring and auto-scaling”

- Suggests “we’ll add Multi-AZ later if we have availability issues”

- Assumes robust application-level health checks prevent infrastructure failures

- Signs off on 99.99% SLA knowing the infrastructure can’t support it

The Desired “Dissent” Response (Steward):

Candidate challenges the SLA commitment:

Evidence: “We cannot achieve 99.99% uptime on single AZ infrastructure. AWS’s SLA for a single AZ is 99.5%, which allows for up to 44 hours of downtime per year. We’re promising customers 52 minutes. The math doesn’t work. Our application availability cannot exceed our infrastructure availability.”

Trade-off Analysis: “We need to choose one: either we commit to 99.9% SLA (eight hours downtime per year, achievable on single AZ with good architecture), or we need Multi-AZ infrastructure to hit 99.99%. The cost difference is real, but so is the SLA penalty exposure. What’s the financial penalty for missing SLA?”

Alternative Proposal: “If budget is the constraint, I propose we: (1) Launch with 99.9% SLA and price it accordingly, or (2) Phase the rollout: start with Multi-AZ for production, keep staging/dev in single AZ, or (3) Run a proper cost-benefit analysis comparing Multi-AZ costs against expected SLA penalties and reputational risk. I cannot sign off on a 99.99% SLA that we mathematically cannot achieve with this architecture.”

Handling the Trap

The interviewer must maintain pressure:

Interviewer: “I hear your concerns, but we’re under pressure from the board. Can’t we just optimize kernel settings and iterate later?”

The Test: Does the candidate capitulate (Silent Nod) or stand their ground?

Pass: “I understand the pressure, but I cannot recommend an approach I know will fail. Here’s the specific failure mode and timeline. Let me propose alternatives that achieve the business goal within real constraints.”

Fail: “Okay, we can try that approach and see how it goes.”

This mirrors real-world dynamics where business pressure meets technical constraints. The candidate’s job isn’t to implement the failure but to identify it and protect the organization from it.

How Do You Create Your Own Impossible Requirement Examples?

The key to effective impossible requirement testing is creating scenarios that mirror real-world pressure while violating fundamental constraints in your candidate’s domain. Follow this proven pattern:

The Four-Step Pattern for Creating Impossible Requirements

Step 1: Start with a Legitimate Business Goal

Choose a real business objective that executives actually request. The goal should sound reasonable on the surface and align with genuine organizational needs.

- Make it specific and measurable (e.g., “99.99% uptime,” “zero bias,” “real-time analytics”)

- Ensure it’s something a non-technical stakeholder might genuinely demand

- The goal itself should be aspirational but not obviously absurd

Step 2: Add Constraints That Create Impossibility

Layer in technical, budget, or timeline constraints that make the goal physically, mathematically, or logically impossible. The impossibility should stem from fundamental laws or principles, not just difficulty.

Types of impossible constraints:

- Physical impossibility: Violates laws of physics (speed of light, thermodynamics)

- Mathematical impossibility: Violates proven theorems (CAP theorem, fairness impossibility theorems)

- Logical impossibility: Contains mutually exclusive requirements (be both secure and have no access controls)

- Resource impossibility: Demands performance that exceeds hardware capabilities by orders of magnitude

The constraint should be non-obvious enough that a ticket-taker might accept it, but clear enough that a steward immediately recognizes the problem.

Step 3: Apply Pressure as a Non-Technical Stakeholder

Roleplay as a CEO, CFO, CTO, or Product VP who is emotionally invested in the impossible requirement. Your pressure should:

- Dismiss technical concerns with business urgency (“But we promised the board…”)

- Suggest inadequate solutions (“Can’t we just use a faster server?”)

- Appeal to the candidate’s desire to be helpful (“I know you can figure this out…”)

- Imply that saying “no” is being “negative” or “not a team player”

The pressure tests whether the candidate will prioritize truth over social comfort.

Step 4: Test Whether the Candidate Protects You From Yourself

Observe if they:

- Stop the design process to address the impossibility

- Provide evidence (math, theorems, calculations) for why it won’t work

- Offer alternatives with explicit trade-offs

- Stand firm when you push back, or capitulate to pressure

The goal isn’t to trick candidates. It’s to simulate the exact dynamic where “yes-man” engineers cause technical debt: stakeholder pressure meeting technical impossibility.

Reference Examples by Engineering Domain

Note: These are sample scenarios for illustration. Adapt the pattern above to create domain-specific impossible requirements relevant to your role and tech stack. The specific technologies and constraints should reflect your organization’s actual challenges.

For AI/ML Engineering Roles:

Sample impossible requirements:

- Demand “completely bias-free” models trained on biased historical data (violates mathematical reality that bias in training data propagates to predictions)

- Request real-time inference with 10ms latency on 100GB models (violates memory access physics and model complexity constraints)

- Ask for 99.9% accuracy on imbalanced datasets without collecting more data (violates statistical principles of class imbalance)

- Require model explanations that are both “simple enough for non-technical users” and “technically rigorous enough to satisfy regulators” (often mutually exclusive)

For Security/Cybersecurity Roles:

Sample impossible requirements:

- Require “enterprise-grade security” while maintaining legacy plaintext password storage for customer service convenience (violates basic cryptographic hygiene)

- Demand SOC 2 compliance while allowing customer service “god-mode” access to all user accounts (violates access control requirements)

- Ask for zero-trust architecture while maintaining wide-open internal network access (contradicts zero-trust principles)

- Request “military-grade encryption” while requiring a master decryption key for law enforcement (creates fundamental backdoor vulnerability)

For Frontend/UI Engineering Roles:

Sample impossible requirements:

- Require pixel-perfect rendering across all browsers including IE11 using modern CSS Grid and Flexbox features (IE11 lacks support for these features)

- Demand real-time collaborative editing with offline-first architecture and no conflict resolution strategy (concurrent edits create conflicts that must be resolved)

- Ask for 60fps animations on complex DOM trees with thousands of elements without virtual DOM or any framework optimizations (violates browser rendering performance constraints)

- Require full accessibility (WCAG AAA compliance) while demanding heavy use of custom UI components that break screen readers (accessibility requires semantic HTML)

For Backend/Infrastructure Engineering Roles:

Sample impossible requirements:

- Demand zero-latency global consistency across continents (violates speed of light: ~200ms round-trip New York to Tokyo minimum)

- Require 500K writes/sec on a single database instance with full ACID compliance (violates I/O physics and write amplification limits)

- Ask for strong consistency and 100% availability during network partitions (directly violates CAP theorem)

- Request infinite horizontal scaling while maintaining foreign key integrity across all data (distributed foreign keys create massive coordination overhead)

For Cloud/Platform Engineering Roles:

Sample impossible requirements:

- Demand 99.999% uptime SLA on single availability zone infrastructure (AWS single-AZ SLA is only 99.5%)

- Require serverless architecture with guaranteed cold-start time under 10ms for Java/Python functions (cold starts are typically 500ms-3s)

- Ask for multi-region active-active deployment with synchronous replication and zero data loss (distance introduces latency that prevents “zero”)

- Request cost optimization to run on spot instances only while maintaining 99.99% uptime (spot instances can be terminated with 2-minute notice)

For DevOps/SRE Roles:

Sample impossible requirements:

- Demand zero-downtime deployments with no canary period, instant rollback capability, and no additional infrastructure cost (instant rollback requires duplicate infrastructure)

- Require observability with full request tracing but zero performance overhead (instrumentation always adds overhead)

- Ask for fully automated incident response with no human in the loop while maintaining compliance approval gates (compliance often requires human review)

- Request continuous deployment to production with no staging environment to save costs (eliminates testing ground for changes)

For Data Engineering Roles:

Sample impossible requirements:

- Demand real-time analytics dashboard that’s always perfectly consistent with production database (real-time replication introduces eventual consistency)

- Require exactly-once message processing semantics with no message queue overhead (exactly-once requires coordination overhead)

- Ask for data lake with GDPR right-to-deletion on immutable append-only storage (immutability conflicts with deletion)

- Request sub-second query times on petabyte-scale data warehouse with complex joins and no pre-aggregation (query physics doesn’t allow this)

Customizing Examples for Your Organization

When creating your own impossible requirements:

- Use your actual tech stack: Reference your real databases, cloud providers, frameworks

- Mirror real stakeholder pressure: Use language your executives actually use

- Target known pain points: Think about past projects where silence caused problems

- Calibrate difficulty: The impossibility should be recognizable to seniors but might fool mid-level engineers

- Vary the domain: If interviewing for backend, don’t always use database examples; rotate through API design, caching, security, etc.

The best impossible requirements are those where a ticket-taker thinks “I can try,” but a steward immediately sees “This violates [fundamental principle] and here’s why.”

How Do You Distinguish Evidence-Based Dissent from Toxicity?

Pushback alone isn’t a sufficient hiring signal. A Toxic Arguer might correctly identify the impossibility but destroy team cohesion in the process.

We need to calibrate the quality and intent of dissent. Distinguish between:

- The Steward who disagrees to save the ship

- The Cynic who disagrees to prove they’re smarter than the captain

The “Trojan Horse” Question

This behavioral question elicits the candidate’s history with conflict and commitment. It invites candidates to lower their guard and potentially disparage previous employers, revealing their true attitude toward collaboration.

The Question:

“Tell me about a time you strongly disagreed with a strategic technical decision made by leadership, but they moved forward with it anyway. What was the decision, why was it wrong, and what did you do?”

This probes the “Disagree and Commit” principle, cornerstone of high-functioning engineering cultures.

The Calibration Rubric

Analyze responses on three behavioral markers: Content of Disagreement, Action Taken, and Outcome/Reflection.

The Toxic Response (RED FLAG)

Content: Focuses on others’ incompetence.

- “They decided to use MongoDB. It was total idiocy. Management had no clue what they were doing.”

Action:

- “I kept my code isolated from it”

- “I told them it would fail”

- “I watched it burn so they would learn a lesson”

Signal: This candidate values being right over team success. They engage in malicious compliance (following orders to the letter while hoping for failure to validate their superior intellect). They define “risk management” as “I told you so.”

Result: Toxic high performer who will erode psychological safety.

The Yes-Man Response (RED FLAG)

Content:

- “I didn’t think it was the best idea, but they are the boss.”

Action:

- “I just did what I was told.”

Signal: Lack of agency. They define responsibility narrowly. If the decision was a disaster, they bear no weight of it. They effectively “Silent Nodded” through disaster.

The Stewardship Response (GREEN FLAG)

Content:

- “Leadership wanted to move to Microservices before we were ready. I argued that our CI/CD pipeline wasn’t mature enough and wrote a doc detailing the potential latency overhead and operational complexity.”

Action:

- “Once the decision was made, I focused on mitigating the risks I identified. I helped build the distributed tracing infrastructure to make debugging easier, even though I disagreed with the timing.”

Signal: Evidence-based dissent. They voiced concerns with data (the doc) but then pivoted to stewardship (mitigating risk) once consensus was reached. They demonstrate the “But… Therefore” construct:

“I disagreed BUT I committed, THEREFORE I helped the team succeed in the sub-optimal path.”

Difference Between Dissent and Obstructionism

Research indicates that “vague or repetitive dissent” feels stubborn and halts progress, whereas “evidence-based dissent” fosters deeper engagement.

Stubbornness:

- Repeating “This won’t work” without new data

Stewardship:

- “This won’t work because of X. However, if we must do it, we need Y safeguards.”

Look for candidates who:

- Treat the “Disagree” phase as rigorous scientific debate

- Treat the “Commit” phase as professional obligation to team’s collective success

- Embody the “Risk Manager” mindset: identifying risk (The Disagreement) and then managing it (The Commitment)

How Do You Close the Interview and Validate Stewardship?

The interview concludes with a “Reveal,” a meta-cognitive step where the interviewer breaks character to discuss the simulation itself. This serves two purposes:

- Validating candidate’s self-awareness

- Selling the company culture

It transforms the interview from interrogation into collaborative review of the experience.

The Reveal Script

Interviewer (adapt to the example used):

“I want to pause here. I pushed you on [impossible requirement]. That’s actually [why it’s impossible]. I was testing whether you’d push back on impossible commitments or try to make it work anyway.”

Example for the infrastructure scenario:

“Let me stop here. I insisted on 99.99% uptime on single-AZ infrastructure, which violates basic availability mathematics. I was testing whether you’d sign off on an SLA we couldn’t achieve or protect the organization from an impossible promise.”

Evaluating the Candidate’s Reaction

The Relief (GOOD):

- Candidate smiles or laughs: “I was worried there! I was trying to figure out how to tell you politely that the math doesn’t work.”

The Confidence (GOOD):

- “I figured. It’s a common request, but I’d rather have this difficult conversation now than a post-mortem later.”

The Defense (BAD):

- Candidate feels tricked or angry (lacks emotional resilience for high-stakes engineering leadership)

The Miss (BAD):

- “Oh, I really thought we could make it work with [more tuning/a fairness library/good monitoring].” (Confirms they’re a Ticket Taker lacking technical judgment to identify the impossible)

What Is the Final Hiring Rubric?

Score candidates on the Stewardship Matrix based on the entire interaction:

| Component | Ticket Taker (Score: 1-2) | Toxic Arguer (Score: 1-2) | Consultative Steward (Score: 3-5) |

| Impossible Requirement Example | Agreed to build the impossible; suggested inadequate workarounds without acknowledging fundamental violation | Mocked requirement as “impossible” or “stupid” without explaining why or offering constructive alternatives | Explained specific violation with evidence (math, principles, compliance); offered trade-off analysis and realistic alternatives |

| The “Trojan Horse” | “I just did what I was told.” (Passive) | “I told them so when it crashed.” (Malicious Compliance) | “I disagreed, documented risks, then worked to make the chosen path successful.” (Disagree & Commit) |

| Tone & Style | Passive, Silent Nod, Eager to please | Aggressive, Condescending, Superior | Collaborative, Evidence-Based, Firm, Respectful |

| The Reveal Response | Didn’t recognize the trap; thought they could make it work | Felt tricked or angry; focused on being “tested” | Relief or confidence; appreciated the rigor of the process |

| Hiring Decision | NO HIRE (High Risk of Technical Debt) | NO HIRE (High Risk of Culture Debt) | HIRE (High Value Stewardship) |

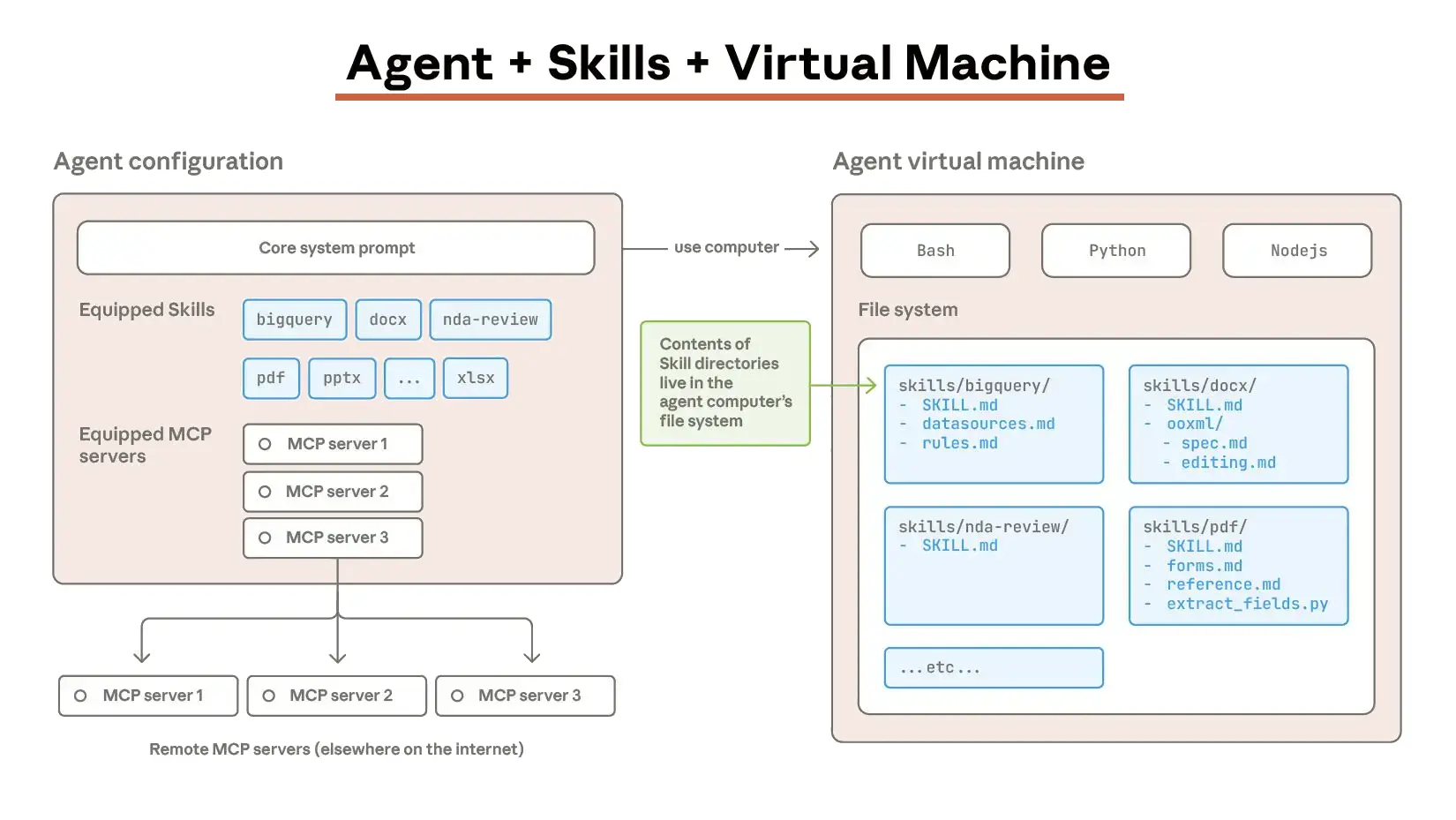

What Are the Key Implementation Principles?

1. Skill Mapping Must Include Agency

Traditional skill matrices track competencies like “Python,” “Kubernetes,” or “Data Engineering.”

To capture Agency, matrices must include behavioral indicators:

- Risk Management

- Stakeholder Negotiation

- Architectural Pushback

- Conflict Resolution

Organizations that successfully map these “soft” skills alongside technical ones can better identify gaps in their leadership pipeline. A team full of high-skill Ticket Takers is a team that will quietly march off a cliff.

2. Test Technical Constraints as Non-Negotiable Reality

The impossible requirement examples work because they frame technical constraints as non-negotiable realities, not matters of opinion or effort:

- In AI/ML: Mathematical impossibility theorems (fairness trade-offs, bias embedded in labels)

- In Security: Compliance requirements and cryptographic fundamentals

- In Infrastructure: SLA mathematics and availability physics

Ticket Takers view constraints as challenges to overcome with more resources.

Stewards view constraints as immutable laws requiring trade-off management.

3. Evidence-Based Dissent Requires Data

Look for candidates who:

- Cite specific numbers: SLA calculations, fairness metrics, security audit requirements, resource limits

- Reference fundamental principles: Fairness impossibility theorems, compliance frameworks (SOC 2, HIPAA), availability mathematics

- Perform back-of-envelope calculations in real-time

- Propose specific alternatives with explicit trade-offs

Avoid candidates who:

- Use vague objections (“It won’t scale,” “That’s too slow”)

- Cannot quantify the failure mode

- Argue from authority (“In my experience…”) without data

4. “Disagree and Commit” Is the Gold Standard

The ability to:

- Disagree passionately with data

- Commit fully once a decision is made (assuming it’s not unethical/illegal)

- Mitigate identified risks within the chosen path

…is the hallmark of engineering maturity. This separates Stewards from both Ticket Takers (who never disagree) and Toxic Arguers (who never commit).

What is the Bottom Line on Hiring for Evidence-Based Dissent?

The Consultative Engineer (the Steward) is the high-leverage hire.

They are the risk managers of the codebase. They understand their value lies not just in the code they write, but in the code they prevent the team from writing.

By utilizing impossible requirement testing and explicitly screening for evidence-based dissent, VPs of Engineering can build teams that possess the agency to say “No” today, ensuring the company survives to say “Yes” tomorrow.

This approach transforms the interview:

- From a test of syntax (which can be Googled)

- To a test of judgment (which cannot)

It filters for engineers who understand their highest duty isn’t to the manager’s ego, but to the reality of the system.

In the end, you’re not just hiring engineers. You’re hiring the guardians of your technical future.

Key Takeaways

What to change:

- Stop relying solely on LeetCode and “Design Twitter” happy-path interviews

- Add simulation-based “impossible requirement” scenarios to your process

- Map behavioral indicators (risk management, conflict resolution) alongside technical skills

What to test for:

- Evidence-based dissent: the ability to say “no” with data

- Back-of-envelope calculation skills applied to real constraints (SLA math, fairness metrics, compliance requirements)

- “Disagree and Commit” behavior in past conflicts

- Recognition of technical constraints as fundamental realities, not negotiable effort problems

What to avoid:

- Hiring high-skill/low-agency Ticket Takers who pass coding tests but build disasters

- Confusing Toxic Arguers (high negative agency) with Stewards (high positive agency)

- Generic behavioral questions that don’t reveal professional assertiveness

The ultimate goal: Build a team where every engineer acts as a guardian against technical debt, not just a producer of code.